It would appear that I'm neglecting this blog, but really I've been neglecting everything in my life apart from uni (including sleep). But the semester is finally over. And so I'm back with an essay I wrote on the Beethoven Ninth. I have to say, I'm extremely annoyed at blogger.com's ability to display the score extracts. In order to kept them within the text block I have to shrink some of them to the point where you can't even read them properly. Anyway to business!

Introduction

Beethoven was one of history’s

greatest composers, so it should come as no surprise that his creative output

contains many turning points. In this essay, I have limited the scope of my

discussion to one work, the Ninth Symphony in D minor. Within this single work,

I have limited my discussion to the final movement. However, this movement

contains two major turning points which have influenced every generation of

composers to be born since its creation, namely the addition of a choral

element to the hitherto purely instrumental symphony form, and the organisation

of the finale into a “symphony within a symphony”.

The choral finale

Beethoven’s Ninth was the first

major symphony to include a choral setting of a written text (in this case Shiller’s

An die Freude). This was a major

turning point as it essentially precipitated what become known as the “War of

the Romantics” or the controversy between proponents of programme and absolute

music.

First, we should examine how

Beethoven went about setting the poem. Interestingly, Beethoven did not use the

entire text, instead he selected parts that suited his purposes and

supplemented them with his own written recitatives.

Joy,

beautiful spark of the gods, daughter of Elysium,

Intoxicated

with your fire, heavenly one, we enter your shrine.

Your

magic power reunites what strict custom has divided;

All men

become brothers where your gentle wing rests.

Be embraced, you millions! Here’s a

kiss for all the world!

Brothers!

Above the canopy of the stars there must dwell a loving Father!

The “programme” thus outlines the

power of joy to reunite humankind before God.

Musically, Beethoven prepares the

vocal entry through the use of an instrumental recitative played by the cellos

and basses:

Moreover, it is these instruments

that subsequently introduce the Freude

theme in full:

When the first vocal soloist

appears at bar 217, he sings a recitative that closely follows the instrumental

version:

The chorus enters with shouts of

“Freude!” before the soloist sings us the first verse set to the theme

previously introduced by the bass section:

The Chorus (apart from the sopranos)

then enters with a repeat of the last couplet:

The significance of the Freude music is that Beethoven has

introduced a vocal element to what had previously been a purely instrumental

genre. Moreover, the way in which he prepared the entry, through instrumental

recitatives, suggested to commentators like Marx that the instruments had subordinated

themselves to the voice. The idea of vocal supremacy is further underscored by the reappearance of

principal themes from the first three movements, which are quickly subdued by

the bass section’s vocally-inflected recitatives. Moreover, the baritone soloist’s opening

words of “Oh friends, not these tones!” would become ammunition for the likes

of Richard Wagner.

Wagner had a lot to say about Beethoven’s

Ninth. He wrote numerous commentaries that touched on the work over a period of

several decades. In fact, his thoughts on the Ninth probably helped develop his

ideas on music in general, particularly with respect to music drama.

In a written programme he conceived in support of an 1846 performance he

conducted in Dresden, Wagner likened the choral entry to “Light break[ing] on Chaos”

with the vocal soloist then supported by the “conquered elements of

instrumental music”.

Thus, like Marx, Wagner saw the finale as the triumph of vocal music over

purely instrumental (absolute) music.

In subsequent writings, Wagner

would develop this idea further by suggesting that Beethoven had developed the

Symphony as far as it could be taken. For Wagner, Beethoven had “matured the

Symphonic artwork to so engrossing a breadth of form”

that it was not even remotely approached by the art of any other age.

In the Ninth Symphony, Wagner saw Beethoven as a mariner sailing out of the

realm of pure music into that of universal Art. Only the “perfect Art-work of

the Future” could follow this path, and that art-form was music drama.

Thus, we can see how Wagner cast

himself as the true musical descendent of Beethoven.

However, not all commentators saw

the Ninth as the end of absolute music. Heinrich Schenker, in particular, sought

to refute Wagner’s interpretation by attempting to show how the finale of the

Ninth could be explained in purely musical terms.

Moreover, according to Schenker, any attempt to invoke literary interpretations

merely reflected an inability to grasp the work’s musical meaning. Beethoven, said Schenker, was keenly aware that the addition of a vocal element

resulted in a contradiction but rather than yield to the demands of programme

music, he attempted to overcome the problem by fulfilling the demands of

absolute music as far as possible. This desire to smooth over the addition of a

foreign element was the reason behind the instrumental recitatives. However, rather

than accepting the Wagnerian view that this demonstrates the supremacy of the

voice, Schenker pointed to the purely musical relationship between the sections

(antecedent/consequent) as vindication of his absolute music argument.

Schenker had a harder time refuting

the baritone’s cry of “Oh friends, not these tones!” which was penned by

Beethoven himself. Under the Wagnerian interpretation, this demonstrates

Beethoven casting off instrumental music as a whole. However, Schenker insists

that the recitative refers not to instrumental music, but only to specific

themes.

It is difficult to see how he could draw such a conclusion without inferring

that he did so out of intellectual stubbornness.

This is not to suggest, however, that Wagner’s argument is unimpeachable. Indeed,

it is obvious that Wagner shamelessly exploited Beethoven for his own creative

agenda, seeking to capitalise on Beethoven’s prestige to lend some authority to

his ideas of nationalism and the “music of the future”. Later in the 19th

century, Brahms would add his two cents by deliberately choosing a theme

reminiscent of the Freude theme for

the finale of his First Symphony in C minor, which Bonds refers to as “an

implicitly vocal finale”.

The obvious inference being that this represented his attempt to reclaim the

Ninth for absolute music.

Although Beethoven included

programmatic elements in some of his works (such as the Eroica and Pastoral

Symphonies in addition to the Ninth) it did not necessarily follow that he was

abandoning “absolute” music. This is aptly demonstrated by the purely

instrumental music that he later composed, e.g. the Bagatelles Op. 126. On the

other hand, the addition of programmatic elements to Beethoven’s works cannot

always be explained in purely musical terms.

In the Ninth Symphony, Beethoven outlined

a possible formal technique for balancing

the seemingly contradictory demands of absolute and programme music. He was not

advocating the choice of one over the other. As such, the Ninth need not have

become a symbolic fork in the road, setting the two Romantic schools on

divergent paths.

There were, at any rate, attempts

by later composers on both sides of the debate to balance the requirements of

symphonic and vocal music, and each of these was greatly indebted to the Ninth.

One example is Berlioz’s Romeo et

Juliette which uses an instrumental recitative (played by the trombones) to

prepare the initial vocal entry. Another is Mendelssohn’s Lobgesang Symphony, which follows Beethoven’s scheme of prefacing a

choral finale with three instrumental movements. Yet another is Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony, which follows the

same outline. Even where the formal design of the choral movement differs, as

is the case with the Mahler, the basic premise in which instrumental music serves as an introduction to vocal music

remains intact.

The form of the finale

The finale of Beethoven’s Ninth was

also an important turning point for more formal reasons. Indeed, there is much

inventiveness in the way the composer constructed the movement. In this finale,

Beethoven brought some previous structural experiments, such as in the finales

of the Eroica and Fifth symphonies

and the Choral Fantasy op 80, to ultimate fruition.

Perhaps the most significant

innovation was to structure the finale as a “symphony within a symphony”. This

interpretation, championed by the likes of Charles Rosen,

holds that the movement functions as both the “finale” of the work and as its

own self-contained four-movement symphony, with the movement divided into

sections that follow the character of symphonic movements.

The first ‘movement’, which runs

from bars 1-330, is expository and dramatic in character. It includes the

instrumental recitatives and vocal entry that were previously discussed. Another

interesting feature of this ‘movement’ is that Beethoven employs a narrative

device to illustrate the search for a new theme (i.e. the Freude theme).

To this end the themes from all

three previous movements are briefly recalled before being summarily dismissed

by the bass and cello recitatives:

First movement:

Second movement:

Third movement:

Although Beethoven had previously

used thematic reminiscences in other works, such as in the finale of the Fifth Symphony,

he had never used it in such a narrative fashion. Commentators have argued that

the use of thematic recollection “serves as a vehicle for linking the vocal

finale with the earlier instrumental movements of the work”.

Moreover, this technique would be borrowed by later composers such as Berlioz

in his Harold en Italie.

The second ‘movement’ from bars

331-594 is a scherzo. As such the “inner symphony” follows the formal design of

the symphony as a whole, with the scherzo being placed prior to the slow

movement.

Musically, the scherzo starts off

with a Turkish March in B flat, with the triviality of this music standing in

contrast with Schiller’s more religiously-based verse:

Brothers, go on your way as glad as

the stars as they hurtle

Through

the heavens, as joyful as a hero on his way to triumph.

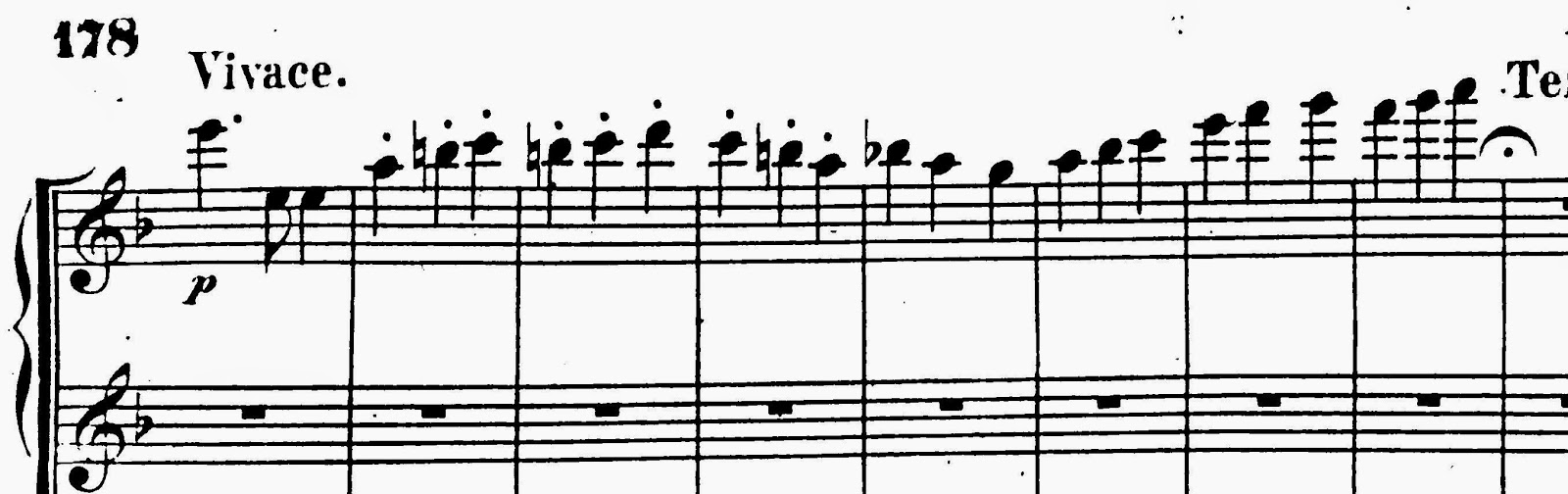

Later, Beethoven develops a purely

instrumental fugue before closing the section with a tutti treatment of the Freude

music in which the chorus is used to full effect:

The third ‘movement’ from bars

595-654 is a slow movement in G major. Even more than the other ‘movements’,

the third is decidedly choral in nature and sounds very much like church music,

particularly where the chorus asks:

Do you fall to your knees, you

millions? World, do you sense your Maker?

Seek him beyond the stars! Beyond the

stars he must dwell!

This has to be amongst the most sublime

moments in all of music:

The final ‘movement’ from bars

655-940 opens with a quodlibet in which the Freude

and Seid umschlungen, Millionen

themes are contrapuntally combined. This section has the loose, joyous and

exuberant feel of a finale and we get the sense that the work will shortly come

to an end.

It is important to note some of the

tools which Beethoven used to achieve this structural double function. The most

obvious one is the use of variation form, based on the Freude theme, almost throughout the entire movement. By using this

technique, Beethoven creates the expectation of contrast in the minds of the listener

and prepares them for textual and tempo changes. Moreover, the use of thematic

transformation to provide continuity between movements would influence the next

generation of composers, such as Schubert in his Wanderer Fantasy and in the

works of Liszt more generally.

Some commentators have argued that

the last movement of the Ninth serves not only a double function but also a

triple function. They argue that the finale also follows a sonata-allegro

design, more specifically that of a classical concerto. Thus, the instrumental and vocal recitative sections form a double exposition, the

B flat Turkish March is the second key area, the instrumental fugue forms the

development section and the move to D major at the Freude chorus marks the start of the recapitulation.

While this interpretation is quite

plausible up the development section, it runs into serious problems at the

so-called recapitulation. The most obvious issue is that the section simply

does not fulfil the requirements of a recapitulation. Indeed the treatment of

the Freude theme as its opening is

the last time we hear the ultimate manifestation of the theme, despite the work

being only two thirds of the way through. Another issue is that the sonata

interpretation does not account for the presence of a new theme – seid umschlungen, Millionen – and key

area (G major) in the recapitulation. Indeed, the addition of new material to a section typically devoted to summing

up is fatal to the sonata interpretation of the movement.

Although there is no triple function

to the form, the presence of a double function has been hugely influential.

Indeed many composers have taken up this design, with notable examples

including Liszt’s Sonata in B minor, Strauss’s Don Juan and Schoenberg’s First

Chamber Symphony.

Conclusion

The finale of the Ninth Symphony

was a major turning point in 19th century music. In this piece,

Beethoven added a vocal element to a previously instrumental genre and in doing

so set the dividing line for a debate on the merits of programme and absolute

music that would consume the Romantic generation. Moreover his experimentation

with a double function structure, in which the finale becomes a “symphony

within a symphony”, would provide a blue-print for future composers to

experiment with symphonic and sonata form.

Beethoven’s Ninth means so many

things to so many different people. However it also marked a turning point for

the composer, who returned to the enlightenment ideals of his youth with the

proclamation (in Schiller’s words) that “all men become brothers"

when reunited by the magic power of Joy.